|

Oregon Mountaineering Association oma@i-world.net - Guestbook - - Join the OMA - |

North Sister - Avalanche - Thayer Glacier Headwall

May 21, 2005

A Final Report is below, after the photos. Lessons Learned are at the end of that report.

Initial Information:

News reports on this are archived on the CSAC Avalanche Center in the Incidents section.

The OMA Climbing Conditions report for the day

The facts that are known are:

- 2 people in a party of four were caught

- the four climbers were Mazama climb leaders

- the climb was not an official Mazama climb

- as climb leaders all had taken an avalanche course in the Portland/Mt Hood area

- both were seriously injured and evacuated by the National Guard

- the group ascended Early Morning Couloir and was descending N Sister

- they were descending the Thayer Glacier Headwall (East Face) (photo)

- the avalanche occured at 8000' or above

- the avalanche happened at approx 1 pm (1300 hr)

- injuries, climber 1: broken pelvis, wrist, and clavicle

- injuries, climber 2: broken tib/fib and an operation on the the other knee

Conditions

There was a climbing conditions report posted Friday night on the OMA website which discussed the current concerns. These included wet unconsolidated snow with minimal surface refreezing, new snow received in the past week, and recent high gusty winds.

The NWAC had also issued a spring statement warning of avalanches on sun exposed aspects on the volcanoes, particularly east facing slopes early in the day.

It was also not difficult to anticipate the development on the existing conditions. The following quote and comment was posted on Cascade Climbers. The quote summarized conditions on a very large scale and was part of an email update by avalanche-center.org

"So even though it is May there are still reports coming in. A lot of the western US, including Colorado in particular, have had very poor refreezing and lack a good melt-freeze base layer. This is also true in the Northwest where the weather is clearing in another day or two. If people venture onto steep slopes in these areas we will see more incident reports. The spring seems unusual many places, as was the winter." --Jim Frankenfield

The above was posted by Jim Frankenfield, Director of CSAC (Cyberspace Avalanche Center www.avalanche-center.org) on 5/22/05. The conditions in the Northwest this past weekend were pretty clear to those who understand snow. It is also true that unless one was there it is not possible to really know why this group made the decision to descend the Thayer. Still, it was poor judgment regardless. --bdog

Despite some claims that the forecast had been good and conditions changed unexpectedly this was not true. All three of the above reports were written, and available, in advance of the climb and all are accurate.

Photos

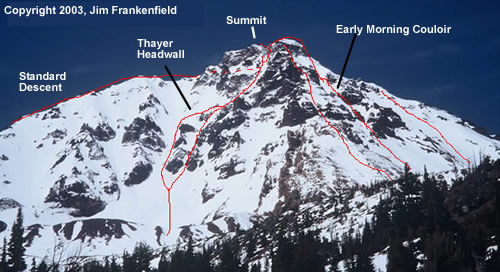

This photo shows the east side of North Sister with both the Thayer Glacier Headwall route and Early Morning Couloir.

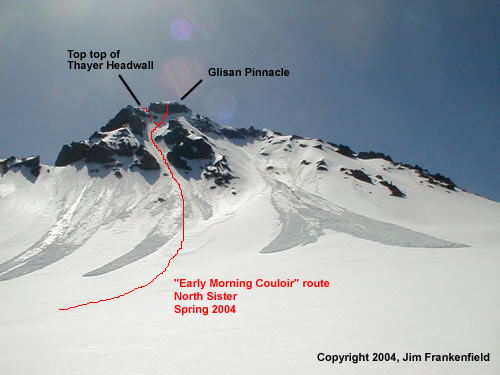

This spring photo shows Early Morning Couloir with Glisan Pinnacle at the top. To reach the true summit (Prouty Pinnacle) it is necessary to climb over Glisan pinnacle. At least one Mazamas group in the past was observed to have traversed to the left all the way around Glisan pinnacle to reach the base of Prouty pinnacle, a traverse which also reaches the top of the Thayer Glacier Headwall.

Final Report

The group consisted of Nancy Miller, 40, James A. Ellers, 36, David Byrne Jr., 39, and James Brewer, 50, all of Portland. All four are Mazamas climb leaders but this climb itself was not an official Mazamas outing. All Mazamas climb leaders are required to have completed a Level 1 Avalanche Course. The Mazamas offer this within the organization through a one day class, despite national guidelines based on 24 hours of instruction. For those that don't do the Mazamas class they recommend Mountain Savvy. All four are assumed to have avalanche training from one of these sources based on their climb leader status.

The climbing objective was the "Early Morning Couloir" route. This receives first sun and would not have been the first choice of many climbers on this day, but the group successfully completed the route and described conditions as good. Rather than climbing over Glissan Pinnacle they traversed around below it to the west and ascended the "Bowling Alley". This is the final section of numerous routes, including the "standard" south ridge. It is a steep couloir (gully) leading up the center of the west side of Prouty Pinnacle. The northern end of this pinnacle is the summit.

They described an abrupt change in climbing conditions when they went from the northeastern slopes to the west slopes. It went from being sunny with warming conditions and softening snow to being shadowed, cold, and icy. It is not unusual for this to be the case and the bowling alley is often hard ice this time of year, requiring crampons and two ice tools for many climbers.

After ascending the bowling alley the group was uncomfortable downclimbing it and sought an alternate descent. The standard descents are the south ridge and the north ridge. The south ridge usually requires a descent of the bowling alley followed by a steep traverse of a snowfield (which is often sun softened by mid-day this time of year). However, the south end of Prouty Pinnacle has been climbed and it may also be possible to rappel down this, especially with two ropes. The north ridge requires either descending the bowling alley or descending loose rock and wet snow to the saddle between Prouty and Glisan pinnacles.

It's not known what the group knew about the various descent options, but they observed two climbers descending the lower part of the Thayer Glacier Headwall and decided that was a viable option. They noted that recent avalanches had occurred since the passage of the other two climbers down lower and they assumed that these avalanches meant that all the snow (or enough snow) had slid, making the slope safe. Nothing more seems to be known about the other two climbers this group observed. They may not have descended all the way from the summit, but this seems to remain unknown.

As Ellers and Miller led, down climbing the steep snow at one in the afternoon, an avalanche released above them and they were carried down several hundred vertical feet to the easier slopes below. The other two had been higher on the slope and were not caught in the avalanche. They may have triggered it but this is also not known for certain.

Ellers described his ride this way:

" ... small slough just took off and grew pretty big in a few seconds. I had a chance to take a couple steps and it was on me. I dropped on my axe but it pulled me off instantly. Then it was over the falls without a barrel, down the Thayer HW, inside the slide. I was under for this point and pretty freaked by the roller-coaster ride. During this time I felt my lower legs break. After the slope mellowed I got my arm out, then kind of just peeled the slide off and got my upper body out as it slowed down. I hadn't tumbled, but remained upright, just rotating from self-arrest to sliding on my right hip to sitting on my butt when I stopped. Nothing was buried except my lower legs.

I took stock and realized my left leg was "mildly" broken and right leg was tib-fib. I got my pack off and threw on my DAS, then started dealing with my leg. I tried moving the right foot to splint it but figured I'd wait a bit and see if the cavalry showed up, as it was a bit sensitive.

One partner had gotten pulled down with me and was a 150 yards or so uphill of me. I could just see her out of the corner of my eye."

The rescue will not be detailed here. The two climbers not caught reached the injured two, assisted them, and called 911. The Camp Sherman Hasty team set out on foot, the National Guard set out by air after a longer lead time. Both groups arrived more or less at the same time and the injured were flown by the Guard to the hospital in Bend. Rescuers noted the dangerous conditions. The Hasty team reported sinking up to their waist in wet snow in places, and the Guard reported observing large avalanches in the same area later in the day after the evacuation.

Lessons Learned:

Here are some things others can learn from this accident:

1) Trip Planning and Route Selection is of the utmost importance. This accident, like many others, could have been prevented with a better choice of destination for the conditions. If you take an avalanche class that does not emphasize the importance of this then take another one that does. It's hard to overemphasize this point.

2) Know the descent options and routes when climbing. Many accidents occur when climbers are unfamiliar with a descent route or choose a poor one. In some cases they are unaware of better alternatives. Consider options in the case of conditions beyond your ability. This is another planning issue and should be researched ahead of time. The group was not comfortable with the difficulty of the standard descent routes once they were on the summit.

3) Don't base your decisions on the actions of others. Just because two others are on a slope or have recently been on it does not mean it's currently safe. In spring the conditions change rapidly under the influence of the sun. In a previous Mazamas avalanche accident on Mt Hood (with fatalities) there had also been another group just a little bit ahead that was early enough and lucky enough to make it.

4) Recent avalanching does not indicate stabilization - it should be taken as a red flag. It takes a lot of avalanches for the snow to be removed from a face such as Thayer Headwall. Or West Crater Rim where the above mentioned accident occured and this same mis-interpretation was made. This is identified as basic and important red-flag information in any good avalanche class and it is frustrating that the same error is being made by the leaders from the same group in repeated accidents.

5) Never have some people above others on a potential avalanche slope. This is a basic rule every avalanche class should be covering, along with one-at-a-time on a slope when possible. In this case they could not go one at a time due to the length of the slope, but having two climbers uphill of two others on a slope like this in these conditions should be avoided. The two that were higher on the slope were not caught. If the other two had been at about the same level they may not have been caught either, and if they were they would have been near the top of the avalanche with a much better chance of escape.

6) In spring conditions sinking deeper than your ankles is an indicator to stop and consider things. Certainly sinking to the waist is another major red flag.

These reports were prepared from numerous sources including news reports, rescue group reports, a report posted on a forum by one of the climbers, and personal experience on and knowledge of the mountain. They were written by Jim Frankenfield, whose first Oregon Cascades route ever was a solo ascent of the direct west face on North Sister. Since then he has soloed Early Morning Couloir, climbed the Thayer Glacier Headwall, and made several ascents and descents of the standard South Ridge, including trips leading novice climbers. He has also circumnavigated the mountain on skis.